Everywhere: elephant sculptures, wall hangings, digital wallpaper, and pictures. They are not realistic elephants but stylized, painted gold on red backgrounds, woven, or carved in stone. They might have human bodies that sit Buddha-like, wearing clothes and jewels, or dancing. The one essential is that they must be pictured with their trunks curling upward. That’s what makes them lucky. Maybe a pair of symbolic elephants, facing outward, flanks your front door; that’s good feng shui. Or you touch your lucky elephant’s trunk for good luck.

Elephants as a symbol evolved from places where elephants live, and that is India, Africa, Burma, and Thailand. Americans and Europeans see them in zoos and circuses, and marvel at their majestic size, but don’t count them lucky or divine. Quite the opposite. Elephants have lost the exotic mystique they had when the King of Siam kept a stable of rare white elephants—so costly to feed and maintain that any possession that took too much maintenance got labeled a “white elephant” and unloaded, by its owner, at a “white elephant” sale. That sounds old-fashioned. But so is the elephant as a New Age lucky charm. If you think elephants with raised trunks are ancient symbols of good luck, read on.

A Sacred Animal

Indian royalty rode on elephants, the luxury transportation of their time and place. For 4000 years in India and Burma they’ve been tamed and used as work animals for logging and hauling, and still are. Quieter and more mobile than machines, they don’t pollute the atmosphere. Always, they are very expensive and require a full-time attendant.

They’ve also been used for long-distance travel that no horse could accomplish, and for war. Their presence intimidated enemy soldiers, and from the back of an elephant several archers could shoot arrows down on the opposition. Still, elephants are trainable only to an extent and in the chaos of a battle could become frightened, resulting in an elephant stampede.

Hinduism’s five sacred animals are the cow, monkey, tiger, snake, and elephant. They are sacred not in themselves—Hinduism is not animal worship—but because Hindu gods can take the shapes of animals. India’s “sacred cow” is the most famous, but Westerners don’t have the same feelings about cows. Instead we’re discovering the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganeesh or Ganesha, and what people like best is that he is the god of prosperity, and we definitely want him and his kind around.

The Elephant God

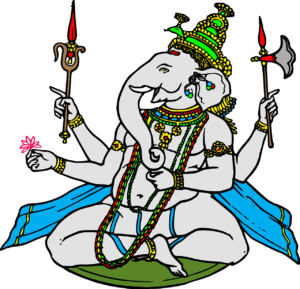

Lord Ganesha only part elephant. Like Shiva and Shakti, he is one of the active god and goddess embodiments of Hinduism’s one god. Most gods keep their human shapes (maybe with extra arms), but Ganesha has a human body and an elephant’s head, which replaced the human head he lost by accident.

Nobody rides him; his “vehicle” is a mouse, and a mouse is almost always hidden in any painting featuring Ganesha; look hard. The mouse can magically bear Ganesha’s weight and takes Ganesha into small spaces so Ganesha can bestow his blessings where elephants can’t fit.

He is called the “Lord of Obstacles,” and when you request his help he invisibly goes before you on his two human legs, carrying his two-headed axe and clearing the way. He is the god of beginnings, ritually honored at the start of events or when buying a new car or house, and also he’s the god of learning and creative arts. He’s often shown dancing, and legend says he broke off one of his own tusks to use as a pen.

Ganesha is a cheerful, playful god, the most popular among Hindus and adopted by Buddhists, and that is how elephants became lucky symbols in the Chinese art of arrangement called feng shui. Hindus delight in Ganesha, also called Ganapati, and hold a ten-day annual festival in late summer and a birthday celebration in winter. Ganesha has a belly because he enjoys worldly pleasures, especially sweets. To obtain his favors, offer him along with your prayers a bowl of sweets. A virtual temple to Ganesha, with music, is available as an app.

Elephants became sacred because they are large, expensive, and very intelligent. They were sacred long before the god Ganesha came on the scene. He is one of the more recent Hindu gods. While his parents Shiva and Parvati are thousands of years old, Ganesha doesn’t appear in India’s pantheon until about 400 to 500 years A.D. He soon developed his own following. When Hindu beliefs and wisdom came to the West in the 1960s, Ganesha came along, but he did not become celebrated and a New Age symbol until the 1980s, when word got out that he was the god of prosperity.

Some nuances were lost in the translation. If you have a home altar, your Ganesha should be seated, not dancing or reclining. In Hindu tradition, Ganesha is a role model.He has large ears and a small mouth. His eyes are narrow, for concentration. His belly digests all, good and bad. Ganesha is always relaxed, so he is almost never pictured with his trunk uplifted; that would be effortful. It’s normally pointed downward, often aimed toward his bowl of sweets.

The Trunk Issue

In India, the position of Ganesha’s trunk is definitely an issue. Articles appear in newspapers explaining what it means when Ganesha has his trunk curled to the right, left, or front, and why believers and fans should choose their Ganesha carving carefully.

What matters in Ganesha worship is not the tip of his trunk, but what direction the trunk is taking when it starts in Ganesha’s face. For home use, Ganesha’s trunk should go leftward. Its energy is feminine and gentler. In temples, it goes rightward and has masculine energy. Idols and sculptures with Ganesha’s trunk in the middle are few and nontraditional.

The up-curled trunk does not come from India, nor is it one of Ganesha’s traits. It’s from a 1930s fad for “lucky elephant” knickknacks. The poverty during the Great Depression spawned many “lucky charms” and “bad omens” that survive into our own times. The lucky rabbit’s foot is from the 1930s, as are the superstitions about spilled milk and walking under a ladder.

We moderns inherited elephant-knickknack fever and our great-grandparents’ ideas about elephant trunks, and here we are, wanting elephant carvings, with upraised trunks, for luck and money. What’s different about us is our belief that luck and money are the same.